(Stick A Flag In Your Yard, Redux)

In 1970 the Vietnam War was unpopular.

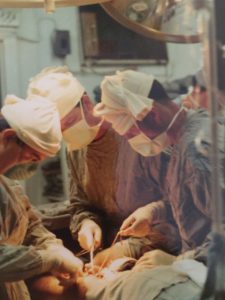

My father was a medical resident, specializing in orthopedics, and therefore excused from military service as part of The Berry Plan.

The draft couldn’t take him.

Still there was an unconscious sense of honor and duty that ran deep in my dad—an unspoken expectation. His father had been a Lieutenant in the Navy and his grandfather had served in the Merchant Marines, and his great grandfather had fought for the Union in the Civil War.

Deep down he felt a little guilty as if he wasn’t doing his part.

But there was more, too.

He’d started to second-guess what life would be like as an orthopedic surgeon. Part artist, part scientist, he couldn’t imagine being tied to the hospital in the way that orthopedics would demand. He wanted to be like his father, a schoolteacher, who had never missed dinner with his family or a kids’ sporting event. He wanted to build stonewalls and wooden boats, to paint pictures, and to see his children’s soccer games and track meets.

When his dad had a heart attack, he experienced a prick of panic that made him prioritize his life.

He quit his orthopedic residency.

My father would be an ER doc instead—five days on, five days off—the hospital would stay at the hospital. No on-call. No office hours. No cases at home.

But.

His Berry deferment was gone.

A couple of his recently graduated medical school buddies had been conscripted into the Navy. One was stationed in the Mediterranean and another one was on assignment off the coast of Rhode Island. The Navy was safer than the Army.

He called Washington for his orders.

Do you want them over the phone?

Yes.

His young wife wanted him to call back, to make sure he’d heard it right.

Danang, Vietnam in two weeks. The Marine Corp needed Navy doctors.

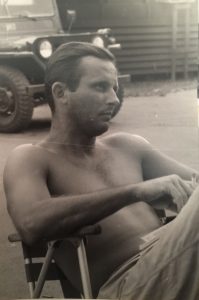

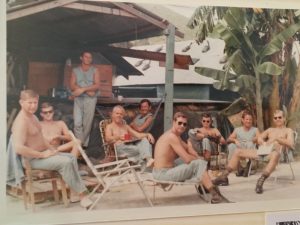

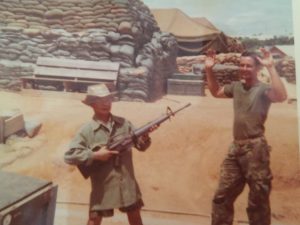

Firebase Ross.

She begged him to run away to Canada. They didn’t speak his last night in the United States. It was a long, quiet flight from Philadelphia to Los Angeles.

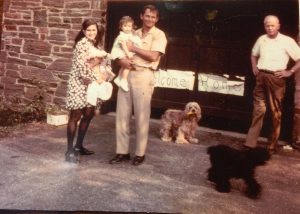

Like M.A.S.H., Firebase Ross was lined in chicken wire and sandbags. He was the head battalion aide surgeon. My mother wrote to him everyday, exaggerating my six-month-old vocabulary. Half way through his tour, he surprised her, calling from Alaska to say he’d be home in twelve hours on a three-day leave (my brother was conceived). But he had to go back. His sister tucked protest books into his care packages.

He served his time.

When he lifted off from Firebase Ross for the last time, he watched helicopter’s wind rip through the rice paddies below. He shifted, his boot knocking against something solid.

When he lifted off from Firebase Ross for the last time, he watched helicopter’s wind rip through the rice paddies below. He shifted, his boot knocking against something solid.

A body bag.

A young man about his age, his brains oozing onto the dirty floor.

They were going home together.

He figured the rest of his life would be gravy.

There was no parade when his plane landed.

No trumpets blared.

Home.

A Lieutenant Commander—the highest rank anybody in our family has ever received.

But they weren’t heroes—those boys who came home from Vietnam. They tried not to wear their uniforms in public lest someone called them baby-killers. They didn’t tell people where they’d been.

It was 1972.

April.

His last day in the service.

He had to report to Bainbridge, MD, a small out-of-the-way town on the quiet Eastern Shore of the Chesapeake Bay for his formal discharge.

Dressed in his uniform khakis, he drove the Baltimore Pike, a road he’d traveled many times as a kid. He remembered this strip of Rt 1 hopping with diners and gas stations. Now it was mostly abandoned. The road was flat and stretched as if it melted into the horizon.

He was ready to put this chapter of his life behind him, to be done with it all.

He stopped at the only diner he could find.

The place was empty and quiet.

Red and white checked tablecloths.

Shiny chrome stools with worn leather upholstery.

Heavy glass salt and pepper shakers.

He sat at the long counter and waited. An older, pretty woman appeared and took his order. He guessed she had inherited this restaurant from her parents. During World War II, she would have been a teenager and the diner probably would have been in its hey day.

The waitress wiped the counter and paused in front of him.

“Were you in Vietnam?” she asked.

“Yes, I was.”

“Was it bad for you there?”

“Not too bad for me. But it was for other people.”

“Yes, I guess it was.” She moved pass him and continued cleaning.

At the cash register when he tried to pay for his meal, the waitress said, “This one’s on the house. We’re proud of you, mister.”

It was too hard to talk. He turned and made it out of the diner before he started to cry.

When my dad told this story, even forty-seven years later, his voice would still catch.

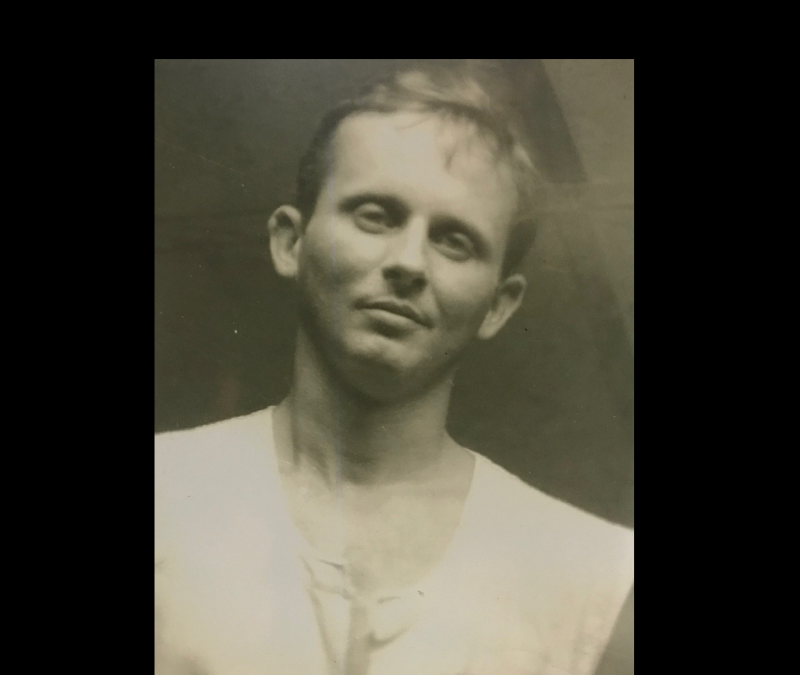

My father is gone now. At the end, he could He barely walk. His hearing was shot. The VA said his Parkinson’s disease was a result of his exposure to Agent Orange in Vietnam. But he had a long and full life. Married for fifty-three years. Four children. Eight grandchildren.

All gravy.

***

David James Christie

July 1, 1941 – February 22, 2019

Reading Eagle Obituary

It doesn’t take a hero to order men into battle.

It takes a hero to be one of those men who goes into battle.

Norman Schwarzkopf

***

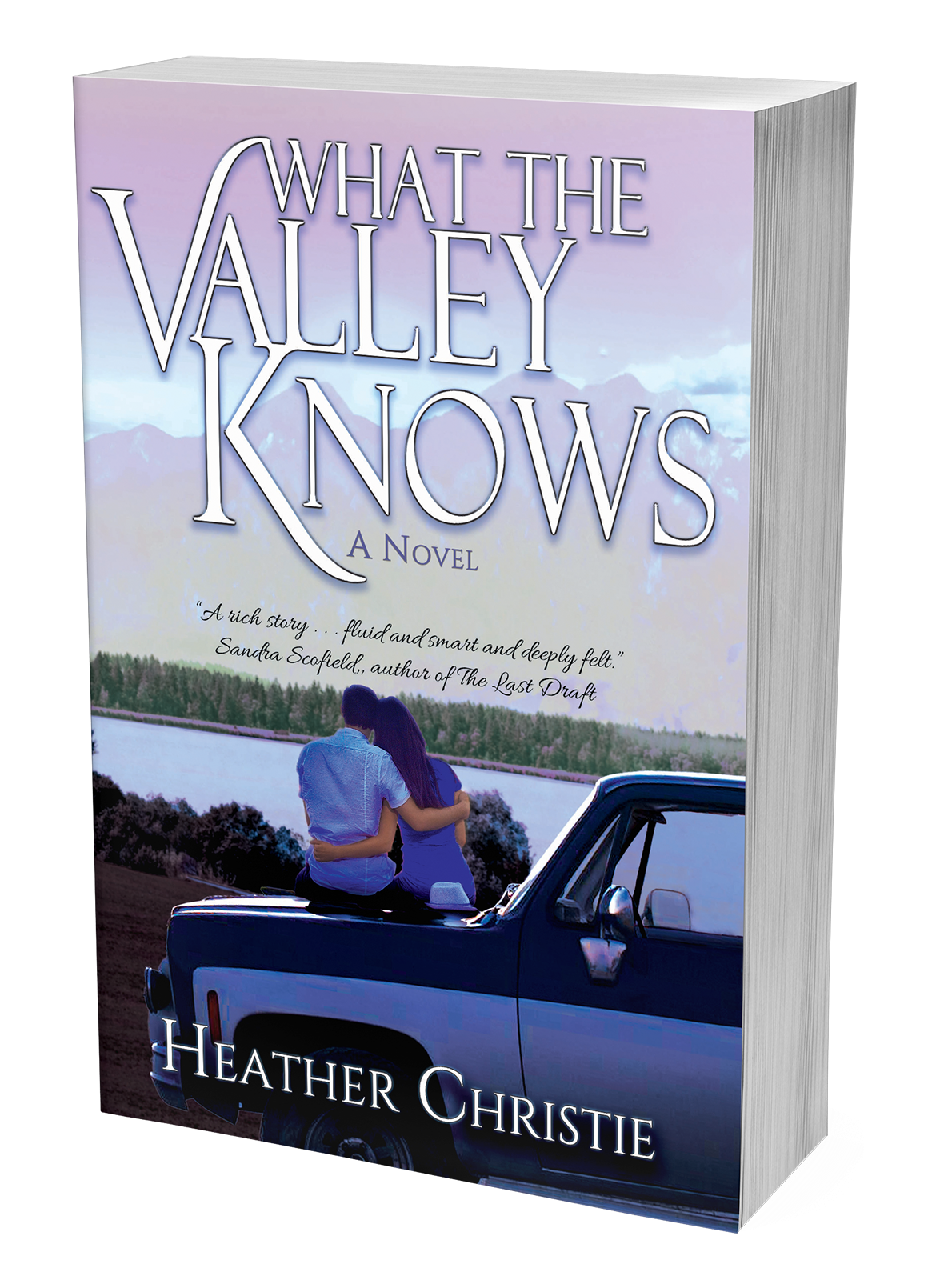

Read the first three chapters of my novel, WHAT THE VALLEY KNOWS, HERE. I hope you love it enough to want to buy the book. Find it on Amazon, Barnes & Noble, or Black Rose Writing. Happy reading!

“A taut, compelling family tale.” Kirkus Reviews

Till next time,

Heather 🙂

Heather- thank you for this story. I am very patriotic and love this country! In my business I am reminded constantly of how lucky we are when my customers who come here from other country’s tell me of their struggles back home. Thank you to your dad , grandfather and great grandfather for serving. Every time I see someone in uniform I shake their hand and thank them for their service. Thank you for reminding me of the importance of that.

Marlene, thank you for honoring our servicemen and women. I will surely pass your sentiments to my dad.

Thank you for sharing your story. When I was in 5th grade my teacher’s son became a POW. She never, ever gave up hope that he would remain alive and return home. When I was in 12th grade I marched in a parade to welcome her son home ~ talk about honor and God’s grace. I was blessed to part of the best home coming ever.

My prayers are with all who serve everyday, not just specific honorary holidays. The families of those who serve are part of the equation that goes misunderstood and forgotten. To raise a family on a day to day basis with the constant fear of losing the love of your life, sister, brother, etc is undeniably a very anxious way to live.

Who helps these folks survive and drys their tears at the end of each day? God does…

What a wonderful, happy ending for your teacher’s family. Thanks for sharing!

Heather

So sorry for your loss

I would like to say that was a beautiful tribute to your dad

Take care

David

Very inspiring story. You must be very proud of your Dad. Heroes come in all forms, but they are all Heroes. Of which your Dad is one of them. Shake his hand for me.

Thanks, Leon! I will do just that.

Powerful. Again, an excellent read!

Thank you to your father and all of our awesome veterans. Everyone should be flying the flag in their honor and certainly for those who sacrificed the most!

Thank you, Darla! I couldn’t agree more.

Thank you for posting this. My first husband, a navy pilot, never came home from Vietnam. Awful war.

I am so sorry for your loss, Barbara. Your family made the ultimate sacrifice. May your first husband rest in peace.

Heather,

Lovely, lovely tribute to the veterans we love ! We’re all so very lucky your Dad and many friends returned from ‘Nam physically intact. No doubt history has shown that war is ugly for everyone. Our gang has heard this same story and viewed the pics over the years; they still elicit deep emotions. And, of course, it’s so typical for your Dad to say ” Not too bad for me.”

Cindy, I was hoping you would like this piece. My father, a man of few words, was so deeply moved by that waitress. Her kindness still brings him to tears.

Your Memorial Day tribute to your father touched me deeply. I was especially moved by the pacing and sweep of your story, holding my breath for his safe return home. I’m thankful to the waitress who acknowledged his service, a rare occurrence at that time, and thankful to you for writing and posting this story of dedication, sacrifice and family.

Faye, thank you. Yes, that waitress, though I am sure doesn’t remember the morning she thanked a guy back from Vietnam, made a lasting impression on him. Thanks for reading.

Great read for today Heather! It brings a very personal touch to what it must have been like to experience life in the military so long ago. Loved the pictures too!

Amy, thanks for reading. My father doesn’t talk much, but this story is one he’s told a few times and I felt compelled to “get it out in the world.”

Another amazing blog!! I will make sure to thank Pop-pop!!

Thanks, sweetheart!

Well done, Heather! Gives all who read it an insight into the quiet dignity with which your dad has lived his life.

Thanks for your kind word, Navy Doc in Rhode Island!

Being part of your Dad’s generation, I watched many friends and neighbors leave for war. Some returned. I and my friends were never of the belief that those who served there should be denigrated. Their stories and their survival are a testament to their bravery and sacrifice. It was the war that was unjust. I celebrate your father and all those who serve.

Peace on Earth!

Thank you, Geri! Yes, peace on earth🌎‼️

What a beautiful tribute to your Dad and all the young men/women that served (and do serve) our country. The story really touched me…another amazing blog!

Thanks, Sandy!

Thank you for sharing your father’s story. My husband and I were students at that time. My husband’s draft number of 221 never got called, but we both knew men who were drafted and sent to ‘Nam. I wore an MIA bracelet for years. Regardless of people’s view of war–particular or in general–those who serve deserve our respect. Please thank your dad for his service for me.

Thanks for sharing, Joanne. I will be sure to pass your appreciation onto my father. Thanks goodness 221 was never called!

What a beautiful tribute Heather! A reminder of a respect and appreciation that we should carry with us everyday. Thank you for sharing your story. God Bless America and all who have served.

Thank you, Nancy!

Great piece, and I also loved the photos of your parents. It made me teary- but most things do : ) I enjoyed reading this!

Thanks, Kelly! Those photos are special to me, too!

Great one- I will make sure I thank him– Awesome!

Thanks, Denise🇺🇸‼️

All of these years knowing your whole family I was in your house 3x’s a week minimum and I wasn’t aware of your father’s commitment to our country,please thank him personally from myself and my family. As always your writing is wonderful Heather!

Thanks, Stephanie! I’ll tell my dad.

My flags are out!!!!!

Heather

What an exquisite tribute to Veterans including your Dad. This is a special reminder for all to show our gratitude daily for these extraordinary men and women. Thank you for sharing your touching piece today.

Lisa, thank for your kind comment. The older my dad gets, the easier his tears come when he tells the story about the waitress in the diner.

Beautiful tribute, Heather. Your pride for your dad and others who serve just oozes–thanks for showing us what that looks like.

Thanks, Lisa! Trying to stay positive about our great country. We all need to pause and be mindful of the sacrifices that others have made for us.

Great blog Mom!!!

Thank you to your Dad for his incredible service and to his legacy which you truly appreciate in bringing his story to all of us in this vivid and evocative post.

Thanks, Faye!

This story is amazing..thanks for sharing. My father served overseas in WWII but never liked to talk about it. I believe he saw abs experienced awful times. He was away for a year and a half from my mother and older brother. Life of a soldier is to be honored. Thanks again for sharing

Thanks for reading, Mary. And thank you to your father for his service to our country.

Thank you, Dr. Christie.

Peace.

Great blog Heather. I did not know this about your Dad. Thank him for his service for me. I have such fond memories of Oley and the Christie family. Give my love to anyone who remembers. Blessings to you and those you love. Charity Quinn

Dear Charity, thank you for your kind comment. We all remember!

Glad I know your Dad- A great man.

I do not know your dad, nor do I know many of the men that served in Vietnam, but the ones I do know all deserve more than what they received when they returned home. Please tell your dad, thank you. Your posts about both of your parents are really touching. I am sure that they appreciate the love that pours out for them in your blogs. Blessings to all veterans of all wars.

Linda, what a beautiful sentiment. Thanks for sharing.

I’m alittle late reading this great piece about #babyboomer #patriotism…about a year? The week prior to Memorial Day 2017, I visited my Dad’s grave to place a flag and was stunned by the overwhelming sea of graveside flags already distributed by the local VA…placed as tribute to the countless fathers, brothers, uncles, sisters, mothers, and aunts for their sacrifice and service to our country. No, I was not visiting Arlington but a cemetary in Birdsboro, just like the countless cemeteries from coast to coast filled with the same graveside flags of honor. I grew up during the protests, flag burnings, and anti war demonstrations. A generation of anti everything “establishment”, loudly claiming freedom from our parent’s values, we saw ourselves as the true “fighters for freedom”. I have enjoyed a lifetime of freedom thanks to those quiet hero’s resting beneath Memorial Day flags. Veterans are the true freedom fighters of our great country and I humbly count myself honored to offer thanks to all yesterday, today, and tomorrow for their service.

Beautifully said, Cindy! Thanks for sharing.

Beautiful cherished memories! They will always remain close to your heart. Thanks for sharing your dads story.

Love, Mary Fidler

Great story. I look forward to reading more.

Beautiful tribute, Heather. I’m so sorry for your loss. You never get over losing a parent, but you do get to keep the wonderful memories and see glimpses of him/her in your children.

God Bless, Sue

So beautifully written for one of the most memorable persons in my career! Dr Christie was one of a kind! So sorry for your loss! Thank you for sharing

What a beautiful tribute. It brought tears to my eyes.

My cousin, Ron, who graduated from Oley, was one of those men who lost his life, and never came back from Vietnam to pick up his life. I was at a young, vulnerable age where I did not process well enough nor understand why. I’m still not certain why, but at least I can now write about this topic. I honor your remarkable dad and all those men and women who stepped up to provide a service. Their courage and bravery is beyond my thought as I’m still struggling still with this issue. Thank you all, who served.

Heather, thank you for sharing about your dad. I’m so sorry for your loss. May your memories of your dad carry through you years ahead.

I remember a few things about your dad from our school years back on Lake road, usually everyone just standing around in the kitchen. I think that’s where everything got figured out. For some reason there’s a Harry Chapin record that also comes to mind. But it was also through your stories that we, your friends came to know him. You, Jamie, Rich, and Tara always spoke heroically of him, always honored him. I hope you’re all together today with full hearts, no regrets, and lots of good stories between you. God bless.

Wonderful story. I had the wonderful privilege of working with both your mom and dad.

As I had written before, I am Honored to have known your Father, He was a “Father” to many of us growing up, and he also was a personal friend to me. I will never forget who he was and how in many ways was a positive role model for us all. It was a shock to find out of his passing, and my heart goes out to the ENTIRE Christie family. I am so very sorry for your loss, if there is anything I can do please do not hesitate to let me know. Please, extend my sympathy to your family. God Bless Dr. David Christie, may he rest in peace!

I proud to have worked with your Dad for nearly 40 years and was honored to have him as a colleague and proud to have called him a friend. He did a lot of good for many people. He will be missed but never forgotten. May he Rest In Peace.

Thank you, Dr. Kershner. It meant so much to my dad that you visited him in the hospital that last week.

Such a beautiful story. I am glad I got the pleasure to meet him. Your parents are amazing people!

Wow, beautifully written. I know your father would be proud. Your family certainly is….

Heather, Sending my heartfelt condolences on the passing of your Dad. I can feel your love and regard from him in every word of this post.